Recently I’ve been trawling through a lot of nineties music. I couldn’t tell you why I’m doing this, or doing this now.

I suspect it’s a subconscious hankering to retain fading memories married with the entirely conscious rationalisation of aging. I’m over thirty now and that means the decline’s setting in. The perception I have of the passing of time is muddied. Almost twenty years seem to have passed in the blink of an eye, yet when I actually think of the mid-nineties, and who I was, all of it seems so distant, an age ago, as if I’m remembering the life of someone else.

There’s an element of morbidity about the past being invariably used to measure the present. No matter how many memories you have of a certain time or place, or what you did, what you experienced, good, bad or otherwise, there’s always an itch of discontented doubt that you didn’t fully immerse yourself in the culture of that time, and that it didn’t leave the indelible mark you believe it could’ve and should’ve done.

This applies to music, and specifically, you wonder what great music you missed and now might never find.

Musically my mid-nineties were mainly about Oasis and Blur, and the rule was you could only confess allegiance to one, or some such bollocks. Then there was being white enough to listen shamelessly or without irony to Cypress Hill records. As an almost bloke, I felt I had to secretly like TLC and En Vogue to retain any notion of respectability, which I subsequently destroyed by purchasing awful Techno and Rave records cut by such luminaries as DJ Fuckface (I checked on Discogs, yep, he’s real). I also remember, and why I remember it god only knows, a pitiful compilation CD of ravey cuts after the scene had become proliferated and homogenised. It was a cynical piece of shit. On one track the bass drum was incessant with a machine gun of high pitched monkey noises, followed by or alongside COCAINE being shouted repeatedly. At least I think that’s how it went – see, not even something as awful as that was enough to leave an indelible psychological scar. I’m sure I still own it, in case you were wondering.

Reading that last paragraph over again, it seems a reasonably eclectic snapshot of the mid-nineties. But in truth any burgeoning experimentation or true examination of a genre was subdued by the staple of that era. Yep, that would be Britpop. Britpop was immersive, if you’re being kind, but for teens of that era, like I was, it was an oppressive entity. Escaping it and or finding the right (read better) music was fraught with problems, such as conforming to peer pressure and just generally lacking refinement, as you tend to at that age.

Another excuse is that this was before the internet. Plus, if you were me, you didn’t have your own money, and you weren’t given enough by your parents to make as many random purchases as you’d like. You were too reliant on word of mouth, and invariably your mate’s tastes largely mirrored your own. The zeitgeist that informed them was formulated through the narrow paradigms of radio, what was charting at the time, or whatever shitty hip magazine shows like The Word were showing that week. Even worse, when you could, in an attempt to break the mould, and be cool, you volunteered yourself as a Guinea Pig, as I did when buying The Orb’s concept album “Orbus Terrerum”. I purchased it based on a mate’s belief that it was something entirely different to what it ended up being. Most likely he assumed it to be comparable to “The Orb’s Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld”. “Orbus Terrerum” wasn’t anything like that masterpiece. If I could describe it, think of a shitty Tolkien pastiche of some dope incoherently narrating what it would be like to traverse through middle earth on a head full of acid. In actual fact that description’s too kind, it mainly consisted of nonsensical ramblings set over dripping tap noises, and generic natural sounds from a swamp marsh. The only explanation I’ll accept is that Alex Patterson was in some borderline schizophrenic stupor from doing a lot of drugs while listening to the BBC’s “Sound Effects No. 17 – Birds And Other Sounds Of The Countryside” on a loop.

We know that nothing can be ubiquitously contemporary, frustratingly more than ever, as we live in today’s multi media age the notion is there that discovery should be instantaneous, but it’s not. Things are always more accessible after the fact. Time passes, but music, once made, exists, often welded to its time, as an artefact of sorts, to be discovered, or not.

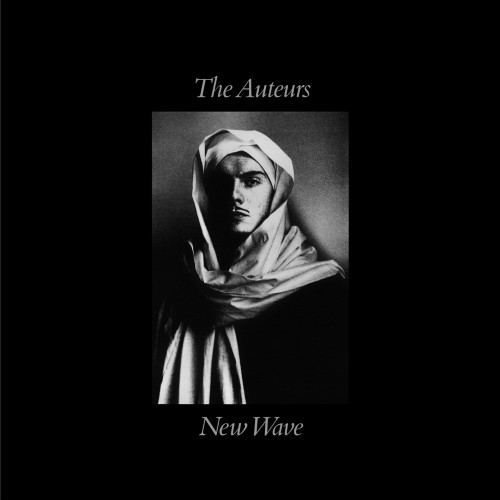

Reissues tend to help. Still, I nearly didn’t bother with “New Wave” as it was categorised as Britpop. This was confusing too, as I’d never heard of The Auteurs at the time. Let’s just say that I was going into this with some scepticism.

In truth what really persuaded me to listen was the band’s name: The Auteurs. It was enticing, and it didn’t strike me as the name a Britpop band would have. Not only was Britpop mostly shit, all the bands, which were fairly or unfairly categorised as belonging to it, had banal names. Even Blur and Pulp, who were good, and in Blur’s case eventually outgrew their association with Britpop, are on the bland side. The Auteurs implies sophistication, or at the very least the intention to be sophisticated and or esoteric, as defined here:

Auteur: an artist (as a musician or writer) whose style and practice are distinctive

As soon as “New Wave” starts it becomes clear that it’s a suitable pseudonym, as Luke Haines’ acerbic take on nineties popular culture, mainly its musical trends and its fads, are laid out in the opening track, ‘Show Girl’. Right from the start you’re hit with the raw penetrating guitar, a standard of the era. Crucially it’s immediately appealing, as it lays the groundwork before dying back, allowing Haines’ captivating narrative to take over. Here he assumes the standard and limited thought processes of human desire within the framework of cultural expectations, which are mainly informed by materialistic need;

I took a showgirl for my bride

Thought my life would be right, yeah

Took her bowling, got her high

Got myself a showgirl bride

Took a job on the side

In a health shop, keeps me well now

Got my mantra for life

Got my karma and a showgirl bride

Were health shops a new trend in nineties? I don’t remember, possibly. Believing in karma, and other daft notions, such as fate and destiny, has been around a good bit longer. In isolation you can’t help but laugh at the idea of marrying a showgirl, but here it’s fitting, as the outcome’s just as preposterous as the process that made it happen.

The final verse shifts to reality smashing the illusion of aspirational thinking, which was glamorised under Thatcherism, ‘She can’t work in the wintertime/And I can’t work any time now/Go to libraries all the while/Looking for a notice by my time’. The nineties were hungover on aspiration, as Britpop, with its associative scene of excess and hubris, became its new acceptable bohemian façade. The idea of marrying a showgirl, who are usually seen as glamorous figures, works cleverly as an additional and appropriate metaphor.

The tone of Haines voice while he dryly and wryly sings ‘All my life, all her life, all our lives/I married a showgirl that’s for life’ helps to convey the sense of disappointment at the realization that this is it, that this is the best you aspired to, that you’ve been conned. He does of course offer no sympathy, and I’ve discovered that cynicism is a recurring theme throughout Haines’ many incarnations, be it as part of a band, or solo, post Auteurs. Haines could be characterizing things in narrower terms on ‘Show Girl’, and talking about specific people when he signs off with ‘don’t you recognize us?’, but I don’t think it matters, as certain aspects of the narrative can be applied in most contexts.

That the composition of most tracks on “New Wave” are heavily reliant on a straightforward guitar lick and percussion is fitting. It’s of its era; unfussy, monotonous, an identikit of many indie bands of the time. The main bridge on ‘Show Girl’ comes dangerously close to Oasis-esque at one point. This is a recurring theme, that by mirroring the sound of the bands of a genre he despised, he was able to make his mockery of them more cutting. I imagine that having been sloppily and lazily tagged as Britpop, Haines felt the best way to mock the genre of Britpop was to infiltrate it.

Whether that’s what he doing with the song ‘American Guitars’ is less clear. Someone or something is a target for his scorn, clearly. The opening verse is scathing of a certain sub-genre’s propensity for mediocrity, ‘They were failing dutifully/If you’re going to fail at all/Failing came more easily/Than it did to us all’. He certainly sings the repeated chorus of ‘American guitars’ with a sneer. The repetitive guitar maxim that punctuates the chorus is mocking too, analogous of the guitar music he’s parodying.

The use of the projective first person only adds to the sarcasm of the monetary rewards for producing crap, ‘Woke up Sunday morning/With a hole the size of my pool/Couldn’t believe I’d grown so ugly/Couldn’t believe I’d been so cruel’. Haines throws a follow up sarcastic barb that he should remember how ‘they’d struggled for their art’. A cutting line that reminds us of how pompous and self-regarding the music industry and musicians can often be.

And so to the candidates? Grunge was big at the time. There was a raft of awful Emo American guitar bands that arrived in the early nineties, like Green Day. The less said about the woeful mainstream bands; Soundgarden, Pearl Jam and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers, the better. Even worse, there was soft alt rock. You know what I mean, right? It was so shite it didn’t even receive a distinctive moniker. Counting Crows is the one band who I recall most vividly from the period. The lead singer sang like a cat being strangled underwater and offered lyrical banalities such as ‘I wannabe Bob Dylan’. Add this mostly vapid mainstream cultural exchange to Britpop and it wasn’t a good era for guitar music, or if you were someone trying to do something different through the medium of guitar based music, to be blanketed under its umbrella. Towards the end of ‘American Guitars’ Haines’ sense of frustration and exasperation at the successes of these sorts of bands oozes through, ‘Thought I knew my place in the world/Thought I knew my art/Glad to be there, see them begin/It was easy to see They were the best band to be in’.

It’s easy to see why The Auteurs were sloppily and lazily chucked into the Britpop chasm when you listen to ‘Idiot Brother’. Jarvis Cocker wished he’s penned what appears to be an odd fable of jealousy, obsession and derision of two brothers, it’s also where we find the album’s best lyric, ‘I was walking around your house/In the middle of the night/Home medicine, erotica/Is your prescription right?’ The song could of course be an analogy of something else, but I do wonder, in the abstract, if it could this be applied to the Gallagher brothers? ‘That’s you and your idiot brother/Waiting in the wing/Which one holds up the other/Which one pulls the string?’ The thought crossed my mind, but only now because I know of Haines’s disdain of Britpop. No act divided opinion more than Oasis, Noel and Liam’s relationship was a point of public consumption and media scrutiny and they were derided by the critics, particularly for their lyrics lacking sophistication and meaning. That the lyrics to ‘Idiot Brother’ are random and lack context, and the guitar work is typical of the template used in an Oasis song, simplistic and offering high pitched pangs, then reverberating to create a wall of noise surrounding the chorus of ‘you and your idiot brother’, just adds to my impression that it could be, and could be is good enough for me.

Speaking of idiocy, Haines was accused of creating The Auteurs as a vehicle to showcase his songwriting talents. It’s an accusation he should readily accept. While he wouldn’t accept “New Wave” being associated with Britpop, the more discerning listener would be able to decipher that it was clearly too good to be associated with it based on the album’s best songs; ‘Bailed Out’, ‘Junk Shop Clothes’ and ‘Starstruck’. ‘Bailed Out’ departs from the electric guitar oriented tenor of the album, leaning on the piano and acoustic guitar with the electric guitar isolated and minimized as the base element. ‘Starstruck’ is a amusing ballad about the generic scenario of a child actor, who’s destined to become corrupted by a sense of self-entitlement a by-product of fame’s ability to distort reality, ‘First child and a showbiz son/Always hide where you come from/Mother got out of rehab and I was born/I was starstruck when I was young’.

‘Junk Shop Clothes’ is the best song on the album, all of Haines’ talent for composition, comedy and melody combine to full effect here. The song glides open to Stranglers Golden Brown-esque strings with sluggishly struck piano keys, it sounds, appropriately, similar to a cheap jingle, before the almost beleaguered tone to Haines’ voice introduces us to the pearl of wisdom that ‘Junk shop clothes will get you nowhere’. You suspect this is a disparaging shot at folk who devolved to slumming it, with the cool bohemian chic of the distressed look, where they appear disheveled and this belies the insufferable mediocrity of them and their middle class affluence, ‘betrayal without treason’. Haines also observes a truth that appearing impoverished for those who truly are is in reality a barrier to social mobility, ‘No summer pavilion, no shooting season/Junk shop clothes will get you/For the rest of your life, you’ll be drunk for the rest of your life’. The cultural references of Lenny Bruce and Chaim Soutine add to ludicrous irony of why fashion slumming is disingenuous, ‘Chaim Soutine never spent a thrift shop dime in his life/Lenny Bruce never walked in a dead man’s shoes, Even for one night’. In case you were wondering, as I did after listening, Soutine spent most of his life in poverty and Bruce’s father was a shoemaker who he seldom saw growing up.

Finding those little esoteric cultural gems, and hidden lyrical nuances, real or projected, on “New Wave” makes me glad I wasn’t aware of The Auteurs during the nineties. I just wouldn’t have appreciated it, and now, years later, this makes it a paradox. The scathing sardonic wit of Haines’ commentary of nineties hedonism and shallowness, and its defective culture, reminds me of how blindly I immersed myself in it. However “New Wave” rekindles memories, which now seen through the prism of Haines’ uber cynicism, has become the antidote to my dismay at past indiscretions. “New Wave” proves the nineties weren’t that bad, especially now you can consume its best facets from a safe distance.

Great piece. I’m old enough to have loved this flawed gem the first time round (on cassette! ) and I’m struck as the years pass how the songs stand while those of their more lauded contemporaries hold little more than nostalgic value. American Guitars and Idiot Brother are personal standouts and I suppose point at what was to come musically.